Wisdom of the Crowd pt. 3

Debrief from the third and final session of the EU's virtual worlds panel

Final recap

The EU asked its citizens what they expect from policymakers on the topic of virtual worlds.

After three weekends of deliberations, the citizens produced 23 recommendations to inform future initiatives.

Following analyses of the first and second, the below summary reviews the final session and the process as a whole.

Programme

Session 3 was back in-person. The first and third days were publicly streamed; the second was open to invited observers.

Day 1: Friday (group 1) & (group 2)

The first day opened with a speech from Roberto Viola, Director-General of the Commission’s DG CNECT department. He said the bloc should aim to “create an experience where you are constantly online but also in touch with reality” and that “no one should be left behind.”

Experts then discussed the “two biggest tensions” the citizens’ conversations had revealed so far, supposedly on digital identity (the question of anonymity) and economic models (centralized v. decentralized) in the virtual world. A Q&A followed.

On anonymity

Mariëtte van Huisjtee of the Rathenau Institute took a “safety-first” position, arguing that anonymity would lead to more hate in virtual worlds. Mariëtte argued, “We need to know who we’re interacting with. No anonymity in the metaverse.”

But Fabien Bénétou, a WebXR consultant, said that anonymity is necessary to protect users’ privacy, warning, “We don’t want to provide information to big companies to help them with their targeted advertising.”

The audience was keen to know what existing laws already covered. Others raised points about annoying login portals and convenience v. anonymity in virtual worlds.

Centralization v. decentralization

Sarah Nicole of the McCourt Institute argued that blockchain—a technology not reliant on intermediate (centralized) authorities—could offer solutions for disinformation, privacy, and monopoly power in virtual worlds.

But Svenja Falk of Accenture said the next generation of the current internet should be centralized even though centralized power “has not helped economies, citizens.”

It was unclear whether citizens were prepared for a discussion on decentralization. One asked, “Will these decentralized worlds be able to make money?”

Citizens’ musings

“I have the impression you were giving broad answers. We are all here to learn things, so we need some more concrete information from you. Could you give us some examples and avoid answers like ‘it’s not black and white’?”

“I must confess, I am a little bit uncomfortable… I don’t know if you’re speaking on behalf of companies or as private individuals… I am just interested in whether this is a lobbying exercise!”

Day 2: Saturday

On the second day, citizens split into 12 working groups (the same groupings from the previous sessions.) Each group had identical agendas but covered 12 distinct subtopics:

The group observed tackled “Connectivity & access for Virtual Worlds” (a provably relevant topic since there was a building-wide WiFi failure at one point.)

The group was buzzing to be back together in person. They even brought gifts (!) for each other, including sweets from Romania and little bottles of Italian liquor.

The task for Saturday was to develop 1-2 concrete recommendations.

First, the group converted broad proposals for their topic into recommendations (what should be done, by who, and how.)

Each group briefly asked questions of two experts, Rehana Schwinninger-Ladak, head of the Commission’s initiative, and Fabien Bénétou. Citizens again wanted to know what existing frameworks were in place (more on this later.)

The group then shared their recommendations with other groups for feedback.

Finally, they fine-tuned the recommendations until they were satisfied with the wording. This was an arduous, if necessary, process. One sleepy fellow admitted, “I am just tired. I have nothing to say.”

Day 3: Sunday

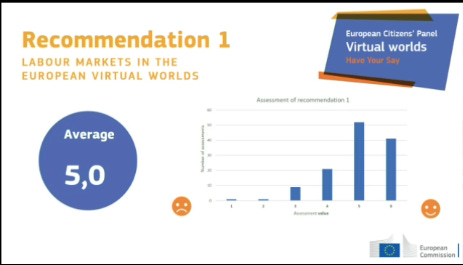

The final day was spent in plenary. The citizens presented and advocated for their group’s recommendations. Then, all citizens scored each recommendation on a six-point scale from 🙁 to 🙂

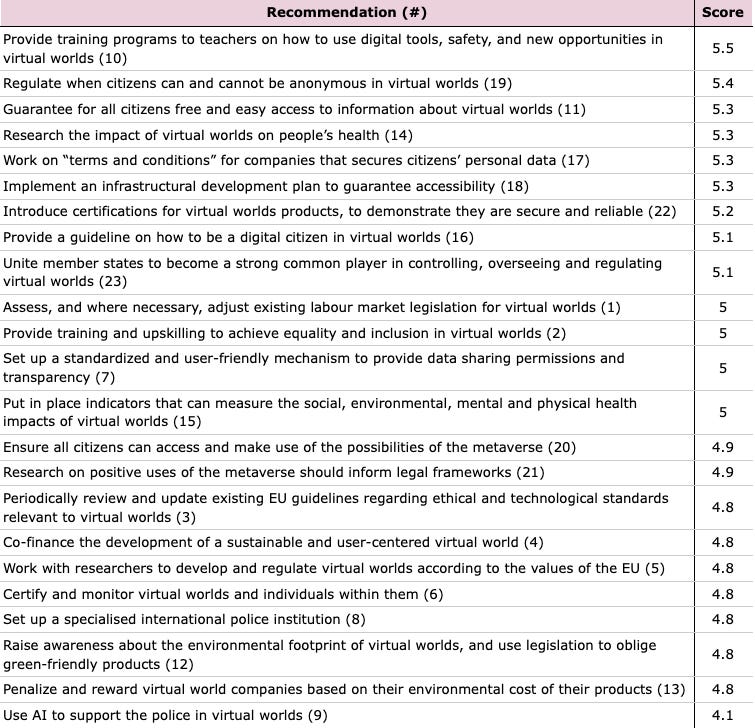

The complete list of 23 recommendations has since been published. Below summarises the recommendations and includes the scores for each.

As the day wrapped up, citizens were given a chance to feedback on the process (more on this below.) The day ended with a lovely anecdote from a Romanian who said they befriended a Belgian through the panel after discovering they could communicate through Spanish—“It is unbelievable how European I felt.”

Analysis

The good

Proof of concept. This is a laudably novel policymaking process. Perhaps nowhere is a comparable dialogue between citizens and their government, a feat made more impressive given the EU’s divergent languages, cultures, and nationalities. There was plenty of praise for this in the feedback session, with one citizen saying, “I would like to applaud the Commission for taking into account the opinion of the citizens. I congratulate you wholeheartedly.” It should inform future experiments.

Final product. The recommendations provided insight into the citizens’ priority concerns with virtual worlds and the tools they expect the EU to deploy. The citizens had plenty of chances to amend the final recommendations and (at least the observed group) were happy they represented what the groups wanted.

Facilitated debate. The organisers did well to create a productive atmosphere among the citizens and ensured they had time to develop relationships and trust. Of course, the point of this exercise was not to sponsor a blind social experiment, but the fact everyone got along meant there were lower barriers to honest engagement. Their direct engagement and frank feedback evidenced this.

The bad

Homogenous expertise

When consulting citizens, the hardest thing to get right is informing them about a topic without influencing their opinions. Unfortunately, concerns about the Commission’s influence remain. Its representatives continued to act as independent experts and consulted the citizens at every stage of the process—as did a few of the other Commission-appointed experts. The risk that an expert’s opinion or bias could unduly influence the citizenry was exacerbated rather than mitigated.

A related risk with reusing a few handpicked experts is that they cannot cover a breadth of topics. This was a notable issue at the final workshop. Citizens focusing on 12 subtopics—from connectivity to international cooperation to sustainability—directed their questions at the same two experts who either had to admit the topic was outside their expertise or gave (by this point) familiar and less helpful advice.

As one citizen put it in the feedback session, “When we’re looking at a topic like policing, really someone from the police should be in the room. If we’re talking about Europol, it would have been useful to talk to someone from Europol. They might have had a different view of things. We need to make sure we have the expertise in the room. Experts, real experts. Not just people who work in these areas in the institutions.”

Shooting in the dark

Before the very first session, citizens were given an information pack about the panel and the topic of virtual worlds. Further briefs on various issues would have been helpful as the citizens dived deeper.

For example, decentralization is a complicated concept that surfaced in the final session without a primer. During this discussion, the audience quickly went off-piste, asking valid but less relevant questions about disinformation, ChatGPT, and TikTok. A fellow observer noted that when not sufficiently informed, citizens resort to broad statements about things they know, like “education is good” and “online spaces should be safe.” But novel concerns and tensions are not addressed.

One citizen said in the feedback session, “It occurred to me that when we had the experts answer our questions, they used terminology I didn’t understand. I almost fell asleep because I didn’t understand a word of what they were talking about.” Another said, “I had the feeling that a brochure would be a good idea.”

Tracking citizens’ overall understanding of virtual worlds would have been insightful. They covered many areas—AR, VR, digital twins, IoT, decentralization—but did not give the impression that they knew how it pieced together. Focusing on specific use cases, such as the digitalisation of public services, might have made more sense.

One citizen closed the workshop by saying, “We’ve come here for three sessions, we’ve talked about a lot of things, but it’s still not clear to me: what is this metaverse, and how will it affect our lives?”

Wider regulatory environment

On various topics, the citizens debated under a presumption of a kind of wild west, only to be later informed in the final session that proposed or existing EU initiatives (DSA, DMA, GDPR especially) already covered the area of concern.

In the observed workshop on connectivity, for example, the citizens spent the day concluding that the EU should ensure its citizens have access to good internet, only for one of the experts to point out that the EU’s Digital Decade Policy Programme already aims to do just this. One citizen said in the feedback session, “During the first weekend, we were given some explanations. It would have been useful to have been told what already exists; for example, the AI Act so that we could build on that.”

The citizens spent so much time rehashing the justification for laws already on the way. It seemed like a missed opportunity to tackle novel issues.

Citizen-washing?

Many external (i.e., non-Commission) observers were not topic experts (e.g., virtual world experts) but experts on participatory democracy. And the sentiment was almost without exception one of disappointment.

These experts were concerned that citizens were hampered by an overly broad subject and ill-prepared for subtopics such as “international cooperation and standards.” The involvement of the Commission alarmed many. One noted that asking a public official for their view on the role of public bodies is a bit like asking capitalists about taxes.

Some of these observers also followed the original Conference on the Future of Europe. This exercise saw over 700,000 European citizens participate in deliberate events through an online platform to decide the priority areas for future deliberations. One observer confided that they were surprised virtual worlds were a topic for one of the subsequent three citizens panels, alongside food waste and learning mobility, since they do not recall the topic mentioned.

The concern is that citizen deliberations become a tool to justify an agenda rather than to formulate one.

The regulatory?

The recommendations gave some indication of citizens’ expectations on the topic of virtual worlds. Their priorities revolve around accessibility and privacy. Interestingly, these diverge from the Commission’s priorities—competition and industrial policy, going on the Commission’s public consultation on virtual worlds.

So it remains to be seen how the voice of the citizens will integrate into future initiatives.

What happens now?

The EU will first publish a report on this panel. The 23 recommendations will inform the Commission’s upcoming communication on virtual worlds, now due in June, and the EU’s more comprehensive work on virtual worlds.