Metaverse EU spoke with Matthew Ball, author of “The Metaverse: And How It Will Revolutionize Everything” and the CEO of Epyllion, a diversified holding company that makes angel investments and produces television, films, and video games.

Ball is also a Venture Partner at Makers Fund, a Senior Advisor to KKR, and a Senior Advisor to McKinsey & Company. He is a board member at numerous start-ups, a contributor to The Economist, and has bylines at Bloomberg, The New York Times, and the Wall Street Journal. Previously, he was the Head of Strategy for Amazon Studios.

We discussed the confusion over the term “the Metaverse”, how to assess adoption, the importance (or not) of better headsets, where policymakers should focus their attention, and what technology a former firefighter wishes he had in his arsenal.

Note: This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Patrick Grady: Apple’s Tim Cook said, “I'm really not sure the average person can tell you what the Metaverse is.” The liberal use of the term has certainly caused confusion. For example, how can someone look at the Fortnite gaming universe and Nvidia’s digital climate twin of Earth and understand they reflect the same trend?

Matthew Ball: The Internet is a collection of standards and protocols supporting the consistent, comprehensive, and coherent data exchange. At first, this data was just structured as plain text. Eventually, networking and computing infrastructure improvements made it possible to share rich media, and new standards emerged to facilitate it.

Reductively, we should consider the Metaverse a 3D augmentation of the Internet. A more advanced description would be a 3D Internet that is also “live” (today, nearly all Internet exchanges use static or old data) and “shared” (today, video games and Zoom are about the only things we co-experience in real-time).

Fortnite is a platform that hosts tens of thousands of virtual worlds and hundreds of millions of users. It is a microcosm of the Metaverse in the same way Facebook, which spans billions of users and pages, is a microcosm of the Internet. Crucially, much of the underlying technology of Fortnite (i.e. the Unreal Engine) also powers other real-world use cases such as self-driving cars, industrial simulations, and so on.

Nvidia’s Earth 2.0 is an earth-scale climate simulation intended to serve as a platform for smaller simulations (e.g., a city, a building, a fleet of cars) not operated by Nvidia.

These two endeavours are largely disconnected, though they reflect the same trends regarding the capabilities, deployment, and relevance of Internet-enabled, real-time 3D simulations.

Grady: Amara’s Law reckons we tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate the effect in the long run. What do you think we are currently taking for granted about the progress of the Metaverse?

Ball: New platforms, technologies, and ideas typically oscillate between bursts of progress and periods of apparent stagnation. AI assistants, for example, began mainstreaming early last decade with Siri in 2011, Google Assistant, and Alexa in 2014. However, they quickly shed users and usage, proving a technological dead end.

In the years that followed, investment continued, and one of these efforts led to the 2017 [machine learning research] paper “Attention is All You Need.” This paper led companies such as OpenAI, founded two years earlier, to fundamentally alter their approach and inspired the formation of other AI companies, such as Anthropic and Cohere. Based on this research, these companies then developed products (e.g., ChatGPT, Claude) that, by 2022, were changing the world.

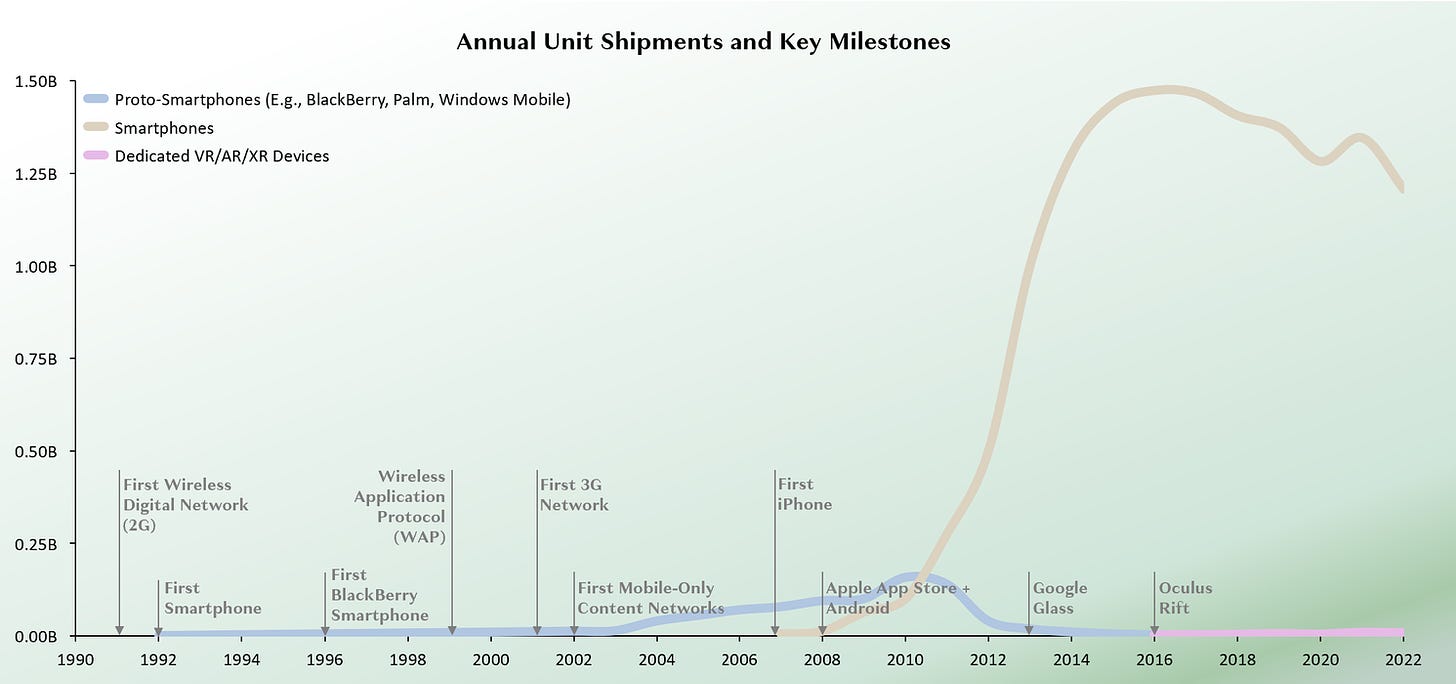

The recent Metaverse craze was prompted by huge technological leaps around 2017-2020, including the rise of cross-platform gaming, high-fidelity virtual worlds on mobile, social gaming, and servers capable of supporting 100-200 people in the same virtual experience. The collection and intersection of these advances were significant.

There may not have been step changes since. Still, there has been sustained progress: the number of regular users of social virtual worlds has doubled over the past few years, there is increasing alignment on standards, many new commercial deals are connecting otherwise disparate 3D networks, and it’s now possible to have a few hundred richly rendered individuals in a complex simulation running on consumer hardware. While headsets remain too expensive, heavy, and technologically limited, they continue to improve materially.

Eventually, these advances will enable a new leap that seems sudden but has been baking for years.

“In 2020, the U.S. had its first-ever live patient surgery using an XR device; there are now several hundred annually.”

Grady: You’ve stated that headsets are not required for the Metaverse but may play a similar role to touchscreens and apps on the Internet. What will this look like in practice?

Ball: In the 1980s and 1990s, it was inconceivable that everyday people would be able to fluidly navigate 3D space using keyboards, mice and touchscreens—but these ‘input models’ have proven surprisingly suitable and scalable.

Today, about 800 million people engage in social, 3D virtual worlds each month, and this sum continues to go up as generational succession occurs. However, it’s still hard for those who didn’t grow up with controllers or iPads to navigate 3D space. Legacy input devices are also limited in what they can do or where they can be used. To most, headsets will increase the number of people who engage in 3D worlds and how often, where, and for which uses.

Smartphones did not require touchscreens. We could have continued to use fixed buttons and click wheels. However, touchscreens—which are easier to use and enable more of a device’s display to be allocated to a specific app—have proved essential to expanding the adoption, usage, and impact of smartphones.

We also did not need to use smartphone apps; instead, we could have used the web browser [as Steve Jobs originally imagined we would]. However, native apps proved a far better and more customised way to run and interact with software.

The same is true for headsets. It won’t always the best way to navigate 3D space, but it’ll often be.

Grady: Policymakers in the European Union have started to examine the impact of the Metaverse on citizens, businesses, and markets. What do you think policymakers should pay the most attention to right now?

Ball: There is still too much focus on regulating products, such as applications and services, rather than application programming interfaces (APIs). Where, when, and how an entrepreneur can compete is based in part on the former but possible through—and crucially, defined by—the latter. This applies to the Internet as we know it, as well as the emergent opportunities of AI, the Metaverse, and more.

Grady: You started your career as a firefighter tackling wildfires in Canada. What immersive technology have you seen being developed that you wish you had at your disposal back then?

Ball: When I was in the field, fire science was just starting to embrace computer simulations. Yet these considered only a few variables, did not run in real-time, did not produce 3D visualisations, and could not really advise on a method of initial attack (where I focused).

All of these have been updated since. And I can tell you that, even as a general sceptic regarding the timeline for headsets to go mainstream, when you use a modern head-mounted display to visualise climatological events and scenarios, including fire management, it’s extraordinary and no exaggeration to say it will save lives.

Matthew Ball’s first book, “The Metaverse: And How It Will Revolutionize Everything”, was published in July 2022 and became an instant national bestseller in the U.S., U.K., Canada, and China. It was also named a Book of the Year by The Guardian, Amazon, The Economist’s Global Business Review, and others.

His second book, “The Metaverse: Building the Spatial Internet,” launched in July 2024 and is widely available. It updates and revises the content from the first and includes entirely new chapters on AI, 3D graphics, and XR.